After Operation Inherent Resolve: How to not mess up US-Iraq security relations again

In mid-September, the Iraqi government announced that it had reached an agreement with the United States to withdraw most US troops from Iraq over the next two years. About two weeks later, at the end of the United Nations General Assembly meeting on September 27, US and Iraqi officials characterized the agreement as a transition in which the military coalition presence would end and the United States and Iraq would transition to a bilateral security relationship. According to both announcements, most US troops would depart by the end of 2025, leaving behind a small contingent in Kurdistan to support counter-Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) operations in Syria. The remaining troops would withdraw by the end of 2026, though those involved in the security cooperation relationship would remain.

Given the conditions of the agreement, many are reasonably concerned that ending Operation Inherent Resolve, the name the United States assigned to the coalition’s counter-ISIS efforts in Iraq, is premature and that doing so could allow ISIS—or another instantiation of extremists—to reconstitute. Moreover, there is concern that the absence of coalition forces could increase Sunnis’ sense of vulnerability, making radicalization easier. A withdrawal would also hand an apparent victory to Iran and its proxy militias, whose continuing attacks against US forces are part of an ongoing campaign to diminish US regional presence.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

Avoiding any of these outcomes will require Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) that are capable of conducting counter-terror operations on their own while remaining interoperable with coalition forces, should ISIS remain resilient. However, a capable, interoperable ISF will not occur in a vacuum. It also requires an Iraqi government capable of containing—and willing to contain—Iran and its militias, which may fill any vacuum left by a defeated ISIS or the departure of coalition forces. Bolstering that political will and establishing that government capability will require further political and economic reforms that Iraqis may not be able to achieve without external support. Thus, any sustainable bilateral security relationship will also depend on active engagement to address the underlying political and economic conditions that fuel instability.

The problem with premature withdrawal

Concerns regarding ISIS’s return are not unfounded. When US troops departed Iraq in 2011, al-Qaeda had been driven from its strongholds in Anbar province, and violence in Baghdad dropped to levels comparable with capitals in other developing countries. In the year following the withdrawal, however, violence increased sharply. Al-Qaeda remnants, facilitated by Iraqi government measures that alienated Sunnis, were able to reorganize, build a following, and, by 2013, metastasize into ISIS. While Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani’s administration is not likely to make similar mistakes, Iranian proxy militias could again be free to engage in the kind of sectarian abuses that enabled ISIS’s rise in the first place.

Likely with that history in mind, General Michael E. Kurilla, the commander of US Central Command (CENTCOM), stated to Congress in March that ISIS could regain lost territory within two years if coalition forces withdraw before ISF can operate independently. Perhaps to diminish this concern, joint US-Iraqi counter-ISIS operations have increased over the last month in an apparent effort to accelerate the degradation of ISIS forces before US forces depart. On August 29, for example, US forces conducted a raid in western Iraq that killed four senior ISIS leaders in addition to ten other militants. Still, according to a July CENTCOM statement, ISIS-related attacks were on the increase from the previous year. ISIS may be down, but it does not seem they are out.

However, while these concerns are not unfounded, they can be overstated. There is likely little the United States could—or would want to—do to change the Iraqi government’s position on the presence of US troops. Iranian efforts to push out US forces and the Iraqi public’s interest in not getting drawn into Iran’s conflict with the United States have placed considerable pressure on the Iraqi government to expel US troops for some time. After the US strike that killed Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani, the Iraqi parliament issued a non-binding resolution for the expulsion of US forces. Pressure to enforce the resolution continued unabated as the United States, Iran, and its proxies have engaged in several escalatory cycles since then.

What has changed, however, is the perception, if not the reality, that the ISIS threat is now manageable and that US forces are no longer needed. During his visit to Washington last April, Iraqi Prime Minister Sudani described the security situation as stabilizing, requiring a transition from military to policing operations. To facilitate this transition, Sudani signed a comprehensive Security Sector Reform (SSR) strategy that aligns with his other economic and social reform initiatives. Under these conditions, US combat forces may not only be unnecessary, but they could also create the impression of instability, undermining the SSR strategy and international and domestic investment critical to preventing ISIS resurgence.

Given the potential for future escalation, continuing to place US troops at risk over marginal gains against ISIS does not make sense. Fortunately, last August, as Sudani was negotiating the end of Operation Inherent Resolve, Iraqi militias agreed to an “undeclared truce” as long as the US forces did not attack them or use Iraqi airspace to attack Iran. At the time of this writing, that truce seems to be holding. It is unclear whether it would last after the withdrawal, especially if the Iraqi public saw US forces as unnecessary.

Sustainable security cooperation

Any sustainable security cooperation program will have to go beyond foreign military sales and a small group of senior advisors to find ways to facilitate the security sector reforms to which the Iraqi government has already committed. The SSR strategy aims to establish a professional, responsive, and flexible security sector to safeguard national security and uphold human rights. To do so, it sets good governance and oversight, capacity-building, administrative and financial reform, and enhancing public confidence in security institutions as its primary objectives. While the goals are admirable, there is good reason to be skeptical that the Iraqis can achieve them, even with US assistance. Twenty years of close security cooperation did not prevent the ISF’s defeat at ISIS’s hands in 2014.

While there are many reasons for that defeat, the US failure to condition material assistance on institutional progress played an important role. So while the United States left the Iraqi military well-equipped, they could not influence leaders at the institutional level to do what was necessary to maintain and employ them effectively. What has also changed this time is the seriousness with which the Iraqi security stakeholders are taking reform. In addition to publicly signing and announcing the SSR strategy, Sudani has directed each ministry and agency to form reform committees, write implementation strategies, and report periodically on their progress. While this effort is just getting started, it provides several opportunities for international partners to engage in the development of effective Iraqi security institutions. Moreover, the SSR strategy clearly illustrates that the Iraqis know what to do, suggesting that future advisory efforts should focus on how to do it.

In emphasizing institutional reform, the United States should also seek to maintain interoperability with the ISF. Given that ISIS resurgence is contingent as much on political and economic reform as it is on military capability, even the most effective security reform effort may not prevent it. In that case, the United States should continue, if not build on, its partnership with Iraq’s counter-terror forces and joint operations command centers to ensure rapid and effective integration of US capabilities should that be necessary. The possibility of ISIS resurgence also suggests expanding law enforcement cooperation as part of the larger SSR effort. When transitioning from military to law enforcement operations, creating law enforcement organizations that prevent ISIS from forcing a transition back to military operations makes sense.

Economic assistance

While security sector reform remains an important area for international assistance, stabilization will require international partners to shift focus to economic and social development. Fortunately, Iraq’s economic indicators seem to improve as the ISIS threat diminishes. In 2023, Iraq’s non-oil sector showed a strong recovery, with non-oil GDP growth estimated at 6 percent, driven by increased public expenditure and agricultural output. However, oil production cuts due to OPEC+ agreements and interruptions in the pipeline with Turkey tempered economic performance. In 2024, economic growth should improve, with the non-oil sectors continuing their strong performance. Iraq’s unemployment rate is around 15.6 percent, up from 8 percent in 2008. However, it has declined from a high of 16.2 percent over the last two years. While the good news is that unemployment is decreasing, underemployment remains a significant concern. Here, too, as evidenced by a White Paper authored by the Iraqi minister of finance in 2020, the Iraqis know what to do, again suggesting that international partners who can focus on how to do it will likely see better results.

The importance of broadening US relations with Iraq beyond counter-terror operations cannot be overstated. China, Russia, and Iran will try to fill any vacuum left by the withdrawal of US forces. No matter how successful US security engagement is, achieving capability and interoperability goals will take time. Thus, without a US military presence, US influence will likely diminish. So, to gain and sustain status as a preferred partner, the United States must find ways to help Iraq solve its other problems. Since a strong economy is often necessary to solve those other problems, it makes sense to start there.

While Tehran is undoubtedly delighted at the withdrawal of US forces, it is also likely time for Operation Inherent Resolve to end. ISIS is degraded, and the ISF has never been more capable of preventing its spread. Additionally, US support for Israel in its war against Hamas and Hezbollah does not simply make US forces a target for Iranian proxies—it creates political friction for Sudani that can undermine the reforms he seeks to undertake. This dynamic does not mean the United States has no role to play; it only has to change to reflect its choices regarding all its regional interests.

Fortunately, twenty years of security cooperation and success against both al-Qaeda and ISIS provide an ample base for a transition to a sustainable bilateral security relationship. As Sudani said when the transition was announced, Iraq is interested in economic and security cooperation with the United States. Perhaps more importantly, Sudani signed over a dozen memorandums of understanding with US companies during his visit to Washington, emphasizing the point. Whether the United States can take advantage of the opportunity presented by the agreement depends on its ability to transition its security relationship from advisor and provider to facilitator. It will also depend on efforts to bolster Iraqi sovereignty to remain resilient against malign influences and capable of the domestic reforms necessary to ensure stability lasts.

C. Anthony Pfaff is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and interim Director of the US Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute. The views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Government.

Further reading

Mon, Jun 10, 2024

ISIS fell, but the conditions that created the terrorist group still exist in Iraq

MENASource By Abbas Kadhim

The pervasive culture of corruption and a poor economy have been among the leading conditions that contributed to the rise of ISIS in Iraq.

Thu, Apr 18, 2024

The KDP is boycotting the upcoming elections. Iraqi Kurdistan may get stuck in an electoral impasse.

MENASource By Sarkawt Shamsulddin

As the June election deadline looms, the future of Kurdistan’s political stability hangs in the balance.

Sat, Jan 13, 2024

Iraq’s prime minister is sending mixed messages on whether US forces should withdraw or not

MENASource By Abbas Kadhim

It would not be an exaggeration to state that US-Iraqi relations are rapidly approaching the dynamics observed under the Trump administration in 2020.

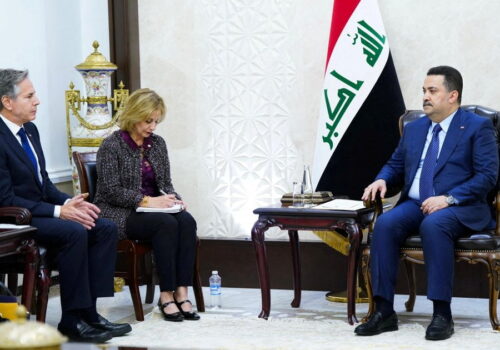

Image: Major General Joel “J.B.” Vowell leaves after the first session of negotiations between Iraq and the United States to end the International Coalition mission in Baghdad, Iraq, January 27, 2024. Hadi Mizban/Pool via REUTERS