China’s support may not be ‘lethal aid,’ but it’s vital to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine

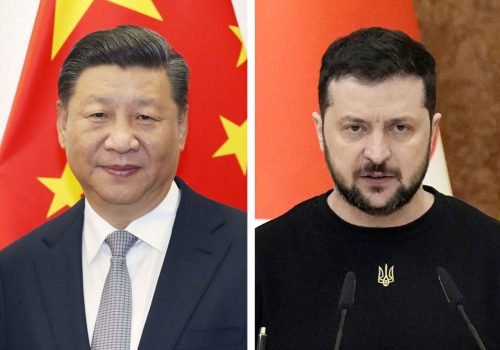

It’s the conventional wisdom in Washington and in most European capitals: China is only providing limited support to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In Beijing, meanwhile, officials attempt to portray neutrality, emphasizing that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is not providing weapons to Russia. As PRC leader Xi Jinping told Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in a recent call, according to state media, “China has always stood on the side of peace.”

Whether or not the PRC crosses the threshold of providing weapons and munitions, often termed “lethal aid,” has become the primary measure of its support for Russia’s war—and the Western rhetoric around this threshold has hardened to the point of becoming a red line. In recent weeks, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan specifically warned the PRC against providing lethal aid. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken then testified before Congress that “we have not seen them cross that line.”

In any event, this focus on lethal aid has come to mean that the vital support the PRC is already providing to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war effort, directly and indirectly, is receiving far less attention. This is fostering de facto US and NATO acceptance of such support, barring the direct provision of military equipment. Let’s be clear: Beijing’s provision of lethal aid would be a new level of escalation, and it should be deterred. However, it benefits Beijing and Moscow for Washington and its allies to focus so intensely on that red line that they fail to stem—or to even fully catalog and condemn—the other support that the PRC provides.

Beijing’s direct provision of equipment and materials critical for military uses, such as transport vehicles and semiconductors, enables Russian military forces to sustain their offensive. The evidence shows that the PRC is already providing critical support for Moscow’s war aims by counterbalancing US and NATO support to Ukraine.

Oil goes out, trucks come in

China’s growing trade ties with Russia are a continuation of a pre-war trend, to be sure, but they also help to sustain the Russian economy and provide materials vital to Moscow’s war effort, counteracting the effects of massive battlefield losses and international sanctions. China’s goods trade with Russia increased markedly just before the invasion began and has continued to increase: In the first three months of this year, Russia-China trade more than doubled from 2020 levels.

The PRC also helps shield Russia’s economy—particularly its vital petroleum export sector—from the full consequences of its aggression against Ukraine. Chinese imports of Russian crude oil hit a record high in March and are likely to rise further. While Chinese refineries opportunistically capitalize on favorable prices due to Western sanctions and price caps on Russian crude, their purchases are politically laden and strategically important. Without these sales, Russia’s limited oil storage capacity would quickly reach tank-top, meaning that Russia would have to shut-in its wells, a process that is costly, difficult to undo, and damaging to long-term production.

In addition to benefitting from oil exports to China, Moscow relies on imports from China, including vehicles. Russia’s severe pre-war and wartime truck logistics limitations underscore that China’s truck exports are providing critical, timely assistance to the Russian military. Russia is likely dual-purposing its imports of civilian trucks from China, using these supplies to fill gaps in its military logistics.

For example, China’s exports to Russia of super-heavy trucks—which are vital for moving heavy military equipment—in December 2022 rose over eleven-fold from prior-year levels. Since trucking shortages often produce inflation, Chinese shipments of super-heavy trucks also helped to keep domestic prices under control, helping sustain Russia’s war economy.

Semiconductors play a critical role

Semiconductors are essential to manufacturing modern military systems, including replacements for the limited stocks of Russian missiles remaining for attacks on Ukrainian targets. In February 2022, the United States and like-minded partners and allies coordinated export controls on Russia, restricting its access to semiconductors. The PRC is undermining the effectiveness of these sanctions by directly and indirectly supplying semiconductors, which removes a key constraint on Russia’s ability to build more missiles. Recent evidence of Chinese parts found in Russian weapons reveals that such dual-use imports from China end up used against Ukraine.

The PRC has also been instrumental in reshuffling semiconductor trade patterns to alleviate Russia’s wartime microchip shortages. According to Chinese customs data, the PRC shipped $179 million of integrated circuits to Russia in 2022, more than doubling its 2021 exports. This does not, perhaps, reveal the full picture. Strikingly, China increased its exports of integrated circuits to Turkey from nearly $73 million in 2021 to nearly $125 million in 2022, despite the Turkish economy’s turmoil. Meanwhile, Turkey increased its exports of integrated circuits to Russia by over 50 percent between 2021 and 2022. This raises the possibility that the PRC, via third parties, could provide or already provides Russia with more semiconductors than is evident from just Russia-China trade data.

Don’t give Beijing a pass

There is some evidence that Beijing is toeing the line on lethal aid without fully crossing it, as a New York Times investigation found that nearly seventy Chinese exporters sold twenty-six brands of drones to Russia since the invasion. While Beijing may continue to stop just short of providing direct lethal aid to Moscow—and it is preferable that Beijing does not cross this line—policymakers in the United States, NATO, and other like-minded countries that are concerned about Russian aggression against Ukraine should neither overlook nor accept the considerable assistance the PRC is already providing Putin.

Drawing the line at lethal aid essentially gives the PRC a pass for enabling Putin’s continued war of aggression against Ukraine. Rather than allow Beijing to evade responsibility as long as it does not cross the lethal aid line, it is time to expose and directly condemn Beijing’s fundamental role in enabling Putin’s continued aggression, and then work to roll back this support.

Markus Garlauskas is director of the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and a former senior US government official with experience as an intelligence officer and strategist.

Joseph Webster is a senior fellow at the Global Energy Center and editor of the China-Russia Report.

Emma C. Verges is a program assistant with the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative.

This article represents their personal views.

Further reading

Wed, Apr 26, 2023

Xi calls Zelenskyy but doubts remain over China’s peacemaker credentials

UkraineAlert By Peter Dickinson

China’s Xi Jinping and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy spoke for over an hour by phone on April 26 in what was the first conversation between the two leaders since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine began more than fourteen months ago.

Fri, Apr 21, 2023

What Russia’s war in Ukraine shows the US about hybrid conflict with China

Hybrid Conflict Project By Gray Zone Task Force experts

As China weighs whether to adjust its tactics to avoid Russia’s failures, the US can look to Ukraine’s and the West’s successes for lessons on how to counter Chinese aggression.

Thu, Mar 30, 2023

Russia faces long economic decline as isolated Putin turns to China

UkraineAlert By Diane Francis

With most avenues for Western partnership indefinitely closed and Russian economic dependency on China growing rapidly, Putin’s talk of “economic sovereignty” is starting to sound very hollow, writes Diane Francis.

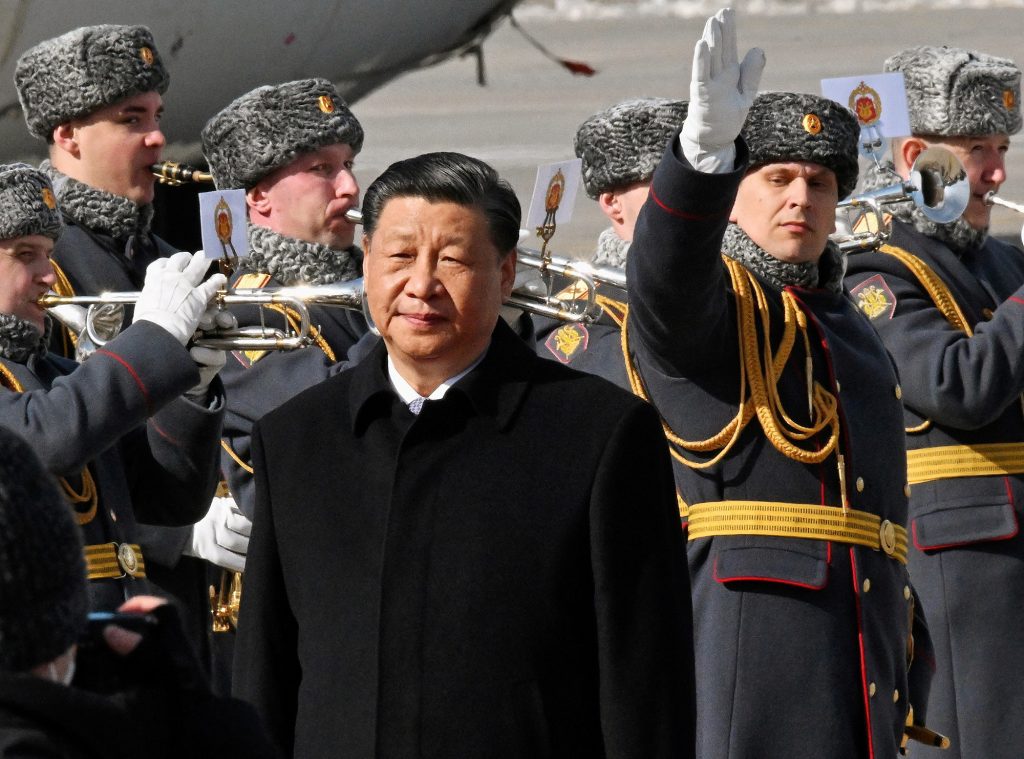

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping walks past honour guards and members of a military band during a welcoming ceremony upon his arrival at an airport in Moscow, Russia, on March 20, 2023. Kommersant Photo/Anatoliy Zhdanov via REUTERS.