In the age of great power competition, the threat of another 9/11 still looms large

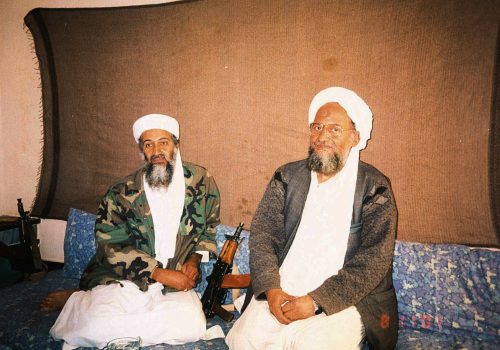

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, marked a watershed moment in global security and the US approach to counterterrorism. The coordinated strikes by al-Qaeda not only resulted in the tragic loss of nearly 3,000 lives but also fundamentally altered US domestic and foreign policy—leading to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the implementation of widespread surveillance measures. In the years since, the United States has not experienced another attack on a similar scale, prompting debates among policymakers and security analysts about the likelihood of such an event happening again.

While terrorist groups still want to execute such attacks, several factors make large 9/11-style operations difficult to pull off. The United States has significantly enhanced its intelligence and security infrastructure since 2001, especially with the establishment of the DHS and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Both of these improved coordination among various intelligence agencies, facilitating better information sharing and analysis and making it more challenging for terrorist organizations to plan and execute complex attacks without detection.

In recent years, the United States has similarly strengthened and expanded its intelligence-sharing efforts with allies to combat evolving terrorist threats. The Global War on Terror (GWOT) sparked the creation of multinational coalitions, intelligence-sharing agreements, and joint operations that have significantly disrupted terrorist networks worldwide. One notable example is the 2019 establishment of the US-led Operation Gallant Phoenix, a multinational intelligence-sharing initiative involving more than twenty countries. The operation focuses on collecting and sharing battlefield intelligence, particularly from the Middle East, to track foreign fighters and disrupt terrorist networks. The participating countries work together to gather and analyze information, which is then disseminated among the coalition to prevent terrorist activities globally.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

The lessons learned from 9/11 also led to the implementation of stringent security measures across various sectors, especially aviation. Enhanced screening processes, intelligence sharing between airlines and government agencies, and public awareness campaigns have created a more vigilant environment, one capable of deterring potential attacks. While terrorists have also leveraged technology for recruitment and communication, the use of data analytics, artificial intelligence, and surveillance technologies has enhanced the ability of law enforcement to detect and prevent potential attacks.

Another factor working against the possibility of another 9/11-scale event is the changing nature of terrorism itself. The killing of Osama bin Laden in 2011 and the dismantling of much of al-Qaeda’s leadership have degraded transnational terrorist groups’ ability to plan and execute large-scale attacks on US soil. Terrorist organizations, recognizing the difficulty of conducting large, coordinated attacks, have shifted tactics toward smaller, more decentralized operations. These so-called “lone wolf” attacks, while still deadly, are typically less complex and less capable of causing mass casualties on the scale of 9/11. The Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, the Orlando nightclub shooting in 2016, and various vehicle-ramming attacks in Europe exemplify this shift in terrorist strategy.

New threats from technology—and from within

While traditional terrorist organizations such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) have been weakened, the threat of terrorism has not diminished entirely. The emergence of new terrorist actors, including domestic extremists, presents a significant concern. Increased political polarization in the United States has led to a rise in violence—and the growth of far-right and white supremacist groups, motivated by hateful ideologies and empowered by social media, has introduced a new dimension to the terrorist threat landscape in the United States. These groups are often decentralized and operate independently of foreign influences, making them harder to detect and prevent.

Advancements in technology, particularly in cyber capabilities, have also opened new avenues for terrorists to inflict harm. Cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, financial systems, or government institutions could cause chaos and mass casualties, though not in the traditional sense of a physical attack. The increasing reliance on technology in all aspects of life has made the United States vulnerable to cyber-terrorism, a growing concern among security experts.

Despite the practical challenges of executing a large-scale attack, the allure of a spectacular event like 9/11 remains strong among terrorist groups. Such an attack would not only cause significant casualties but also generate immense media attention, thereby fulfilling the terrorists’ desire for publicity and psychological impact. The possibility of a well-funded, well-coordinated attack—particularly from a group that manages to evade detection—therefore continues to concern policymakers. The rise of new terrorist groups or the resurgence of older ones, energized by either perceived successes or grievances, could lead to renewed attempts to carry out large-scale terror operations.

Israel’s strongest ally could face terrorist backlash

The United States has been a staunch ally of Israel, providing military aid, political support, and diplomatic backing. This close relationship, combined with the perception of American complicity with Israel’s actions, could increase the likelihood of terrorist attacks against the United States in the wake of October 7, 2023. The portrayal of the United States as a key enabler of Israeli actions contributes to a narrative that the United States is directly responsible for the deaths and suffering of Palestinians. This has inflamed anti-American sentiment, especially in regions where images and stories of civilian casualties in Gaza are broadcast widely. These sentiments are not confined to the Middle East but resonate globally, affecting Muslim communities and Palestinian sympathizers around the world. In recent months, US campuses have become hotspots for intense conflict and occupation by student groups, reflecting the deep polarization within the United States over the Israeli assault on Gaza and the October 7, 2023, attack by Hamas. Pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli student factions have staged demonstrations that often escalate into confrontations, highlighting the deep emotional and ideological divides surrounding these events.

ISIS has historically criticized Hamas for its perceived nationalism and ties to Iran. After the Palestinian group attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, ISIS even refrained from direct comment. The Salafi jihadists have gradually begun to address the conflict and have encouraged their followers to take up the Palestinian cause. ISIS communications, including infographics and an audio message from spokesman Abu Hudhayfah al-Ansari, stress that the conflict should be viewed as a global religious war rather than a territorial one. They advocate for indiscriminate attacks on Jews worldwide, promoting the use of any means necessary, including stabbings, shootings, and vehicular assaults. The influence of these messages is evidenced by a stabbing attack in Zurich on March 3, 2024, in which the perpetrator explicitly referenced ISIS rhetoric.

23 years later, new priorities emerge

Today, the US-led military campaign known as the Global War on Terror is no longer the primary focus of global security discourse, and there is instead a growing sense of fatigue with the West’s prolonged counterterrorism efforts.

The GWOT initially focused on key hotspots such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and the broader Middle East, but terrorist threats have become increasingly geographically dispersed. The rise of groups such as ISIS in Syria and Iraq, Boko Haram in Nigeria, and al-Shabaab in Somalia illustrates how terrorism has spread beyond its traditional strongholds. These groups have adapted to the pressures of global counterterrorism efforts by exploiting weak governance, societal fractures, and economic instability in their respective regions.

The diffuse nature of these contemporary terrorist threats makes them harder to combat through traditional military means. Unlike the early years of the GWOT, when clear targets could be identified and neutralized, threats today are more amorphous and more deeply embedded within local conflicts. The result is a perception that despite significant investments in counterterrorism, the problem persists and, in some cases, has even worsened. The relative decline of counterterrorism as a top priority for the West is also a consequence of the resurgence of great power competition. The rise of China and the assertiveness of Russia have prompted a strategic pivot among Western powers, who now view the actions of these states as the primary challenges to global stability.

The resurgence of great power competition, particularly with China and Russia, has become a central focus for foreign and defense policy. The annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014, the Russian war against Ukraine, China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea, and the growing technological Chip War rivalry have underscored the return of state-based threats, ones that challenge the post-Cold War order. The 2022 National Defense Strategy reflects the transition away from counterterrorism, instead prioritizing “integrated deterrence” and new concepts like “dynamic force employment” and “multi-domain operations” as means to prevent conflict with great powers.

The unfilled national security posts in the Joe Biden administration represent a significant risk in the great-power conflict and counterterrorism efforts, however. The absence of qualified personnel in key positions is a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities that existed before 9/11—a time when the United States underestimated the importance of having a fully staffed and coordinated national security apparatus. These personnel delays have affected more than forty-five senior national security posts, including critical ambassadorships and other roles related to US foreign policy. This backlog has been attributed to political gridlock, with Democrats and Republicans blaming each other for the delays.

While terrorism remains a concern, especially as groups such as ISIS and al-Qaeda continue to pose threats, it no longer commands the same level of strategic priority. The resources and attention previously devoted to counterterrorism are now being redirected to address the more pressing challenges posed by state competitors.

Kristian Alexander is a senior fellow at the Rabdan Security & Defence Institute, United Arab Emirates.

Further reading

Wed, Sep 8, 2021

It’s been twenty years since 9/11. The US Army still hasn’t learned to speak Arabic or Dari.

MENASource By Jon Tishman

The August withdrawal ended close to twenty years of combat operations in Afghanistan, while the US aims to end seventeen years of combat mission in Iraq by the end of this year. After such lengthy conflicts, one might expect the US Army to be overrun with soldiers fluent in Arabic and Dari. Despite repeated deployments and enough time to educate current senior leaders in the ranks from grade school skills to bachelor’s degree-level, the overall rate of soldiers conversant in target languages remains abysmally low in combat arms, even among codified linguist positions.

Thu, Sep 2, 2021

To honor two generations of service members, prevent the next GWOT ribbon

MENASource By Caroline Donnal

Today, executive and legislative actions signal a shift: America’s military footprint in the Middle East is shrinking and thousands of troops are coming home.

Wed, Aug 10, 2022

The founding head of al-Qaeda is dead. But radicalism continues to thrive in Egypt.

MENASource By Shahira Amin

The founding head of al-Qaeda is no longer, but it’s important not to forget that the terrorists that carried out 9/11 were born, raised, and radicalized in Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Image: A U.S. soldier holds photographs of the September 11, 2001 attacks during a ceremony marking the 13th anniversary of the September 11 attacks in the United States, at the Bagram airbase north of Kabul September 11, 2014. REUTERS/Omar Sobhani