Egypt grapples with political uncertainty under El-Sisi

Table of contents

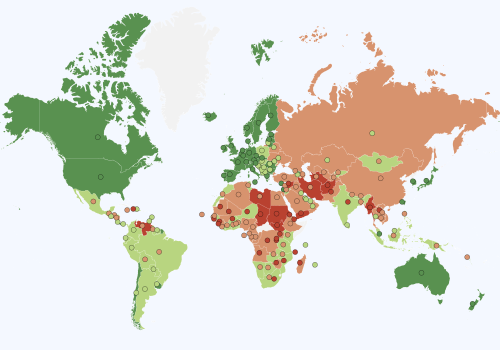

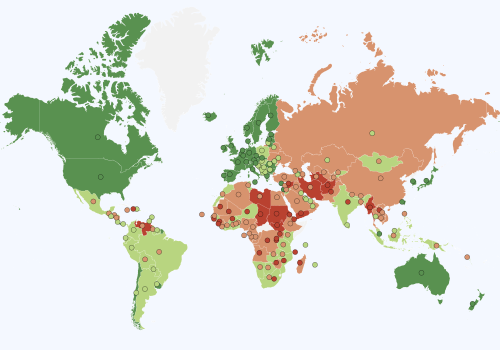

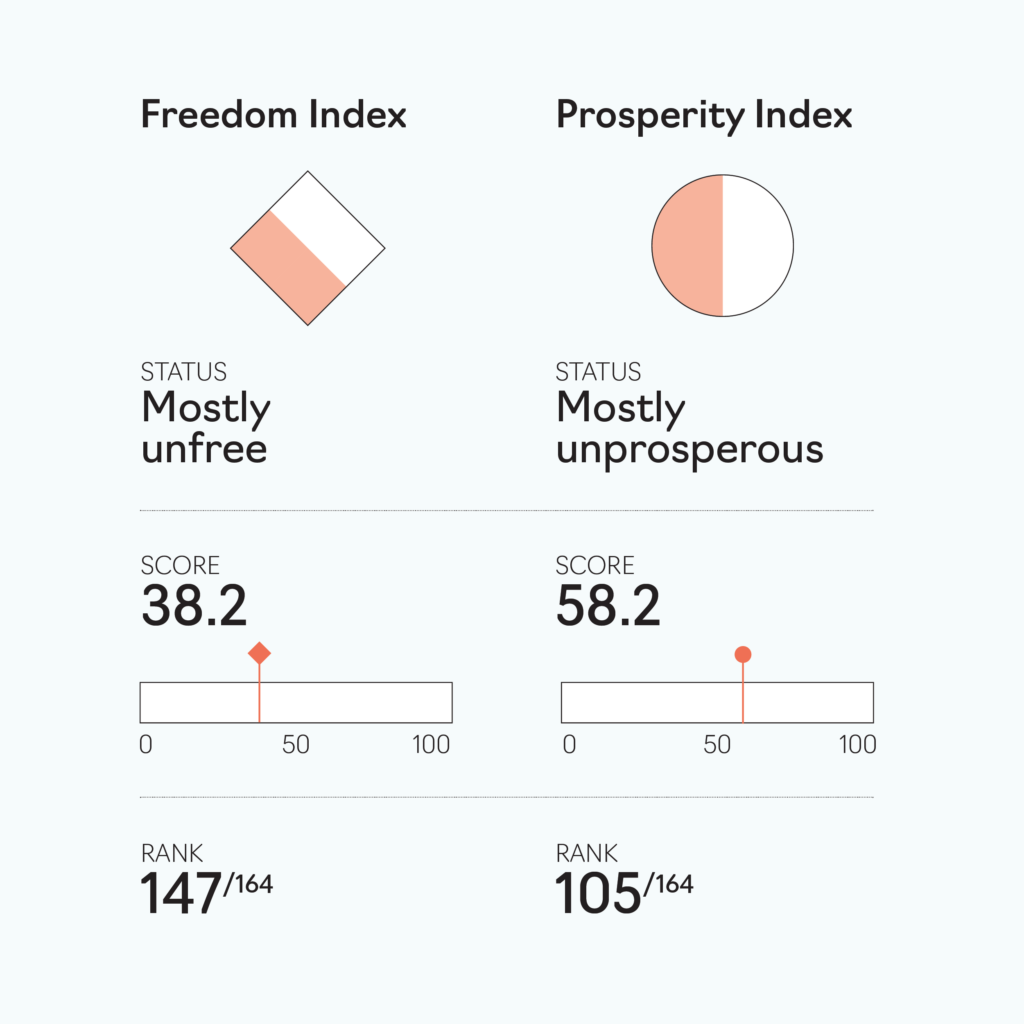

Evolution of freedom

Egypt has experienced a political roller-coaster in the decade following the Arab Spring. The militarization of power in politics has been a key feature of contemporary Egypt. At the end of 2010, massive demonstrations broke out against poverty, corruption, and political repression. These led to the ousting of President Mubarak, a former military officer. This was despite the important economic reforms Mubarak had embarked upon in his last few years in office, which had been lauded by the international community. President Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood movement succeeded Mubarak after free and fair elections in 2012. A year after Morsi’s election, Army General al-Sisi took power in a coup and has since ruled Egypt with an iron fist.

The evolution of the Freedom Index for Egypt is indeed marked by the events of 2011 and 2012. The Freedom Index experienced a steep increase—reflecting the Arab Spring and the free elections that followed—before falling sharply by almost 10 points, a result of the counterrevolution led by General al-Sisi. The political freedom subindex visibly drives the movements in the overall freedom score. The 10-point increase on this subindex in 2011 vanishes, with a subsequent plummeting of almost 15 points, evident in all indicators, but especially in political rights. Al-Sisi has repressed brutally all political opposition and activism.

Economic freedom shows a somewhat erratic evolution, echoing the country’s political instability. Economic freedom seems to improve after 2014 as al-Sisi embarked on a series of reforms. Nonetheless, al-Sisi’s tenure has seen numerous economic problems: The scores on property rights and women’s economic freedom were still extremely low in 2022, and there has been a renewed acceleration toward military control over the economy. Al-Sisi embarked on large infrastructure investments, hoping that these would stimulate durable economic growth. These investments have turned to bad debt. Add to that the fact that the Gulf Cooperation Council countries have significantly reduced their aid to Egypt, making it nearly impossible to repay its ballooning debt and associated interest payments. The country is now at risk of a debt crisis.

Legal freedom presents a clear negative trend in Egypt since 2000, with this subindex losing around 10 points in that time. Clarity of the law, one of the most basic elements of the rule of law, receives a very low score throughout this period. The situation is echoed in the degradation of political freedom and the instrumentalization of the judicial system.

From freedom to prosperity

Just as on the freedom front, Egypt’s prosperity has been a roller-coaster. In what has become a familiar cycle, Egypt typically goes through periods of delayed macroeconomic stabilization followed by a balance-of-payments crisis. The country then calls on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout in exchange for drastic reforms. These so-called structural reforms often consist of cutting consumer subsidies (food and fuel), which helps consolidate budgets in the short run but leaves the structure of the economy—including vested interests and cronyism—unaltered. This, in turn, can lead to social instability and repression. The current episode is no different and does not augur well for addressing the social deficiencies affecting Egypt.

The control of the economy by the army is impeding its rapid and deep transformation.

Egypt’s prosperity score remains significantly below the regional average, although it has seen a sustained increase over the last twenty years, suffering only a small regress in 2013–15. There is still a 3-point gap between the country’s prosperity score and the MENA average.

There has been some limited progress in education, health, and the environment. The evolution of the income and education indicators in Egypt has been somewhat better than the average for the MENA region. In the latter case, Egypt has overcome a differential of 6.4 points with respect to the regional average in 2006 and is now almost 2 points above it. In terms of the health and environment components, the country scores visibly below the regional average, and the gap has actually widened since 1995. Minority rights protection dropped by almost 8 points after 2012, coinciding with the period of political turmoil, but most of that fall seems to have been recovered in the last three years.

The future ahead

Egypt will have to navigate very difficult macroeconomic challenges in next few years. The country is heavily indebted, adding to the already worrisome sociopolitical situation. Egypt is gearing up for elections in December 2023. It is likely that President al-Sisi will be re-elected, and although this would theoretically hand him a mandate for reform, it is unlikely he will do anything that would affect crony or military interests. Instead, al-Sisi might have to resort to further devaluation of the currency, which will ignite further inflation and hurt vulnerable households. What is more, it would create a damaging currency imbalance, adding to the cost of servicing foreign debts that are held in foreign currency.

Al-Sisi will have to find external sources of financing outside of capital markets, given the prohibitive spread on external borrowing. Financial aid from Gulf countries, which typically provided a lifeline, is no longer forthcoming. Gulf countries are looking to invest in strategic assets but also want to see reforms before doing more to support the country. Gulf partners are counting on the IMF to push for more market-oriented reforms.

While political reforms are unlikely given the current circumstances, deep economic reforms also seem doubtful. Indeed, they would be difficult as the militarization of politics and of the economy is entrenched. This stalled situation will continue to limit the country’s potential. It is imperative to re-embark on a balanced economic and political transition to avoid the domestic instability that could result from a frustrated youth. What is more, the geopolitical situation is also tense. The renewed escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict risks spilling over into Egypt. That could destabilize the country and spread to the whole region.

Rabah Arezki is a former vice president at the African Development Bank, a former chief economist of the World Bank’s Middle East and North Africa region, and a former chief of commodities at the the International Monetary Fund’s Research Department. He is now a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Studies and Research on International Development and at Harvard Kennedy School.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: Egyptian men display their ink stained fingertips after casting their votes for a referendum on constitutional amendments at a polling station in Cairo March 19, 2011. Egyptians began voting on Saturday in a referendum on constitutional amendments which the military rulers hope will open the door to elections within six months. REUTERS/Amr Abdallah Dalsh (EGYPT – Tags: CIVIL UNREST POLITICS)