Global China Hub Newsletter: Refusing to act speaks louder than words

Subscribe to the Global China Hub

On October 7, the world witnessed a barbaric attack on Israel by Hamas terrorists. We also received unequivocal confirmation of China’s unwillingness to take risks on the global stage commensurate with its bid to be viewed as a leading power, even in support of a supposed friend.

Beijing has enjoyed some adulation in recent months resulting from its nominal role in brokering a Saudi-Iran rapprochement and stated willingness to facilitate Middle East peace. But, much like Beijing’s proposal of a 12-point “peace plan” for the Ukraine war and refusal to condemn Russia’s aggression, China’s weak response to Hamas’ vicious attack and fallback on ill-timed calls for a two-state solution is craven self-interest dressed up as neutrality.

Beijing seeks the mantle of a trusted peacemaker and “responsible great power” opposed to aggression – and dedicated to stability and sovereignty. But, as senior fellow Jonathan Fulton writes, China remains primarily driven by narrow economic interests in the Middle East, as in much of the world beyond its periphery. This remains true even as China places greater strategic focus on the Global South – witness the Belt and Road Forum kicking off on October 17, which we will address in detail at an upcoming event on the 23rd. Grandiose rhetoric aside, Beijing is unprepared and unwilling to act like a global leader when the chips are down, demonstrating the hollowness of its messaging.

This gap between China’s narrative and its actions plays out in its “sharp power” approach to many of its foreign relations, including with the United States, as Tiff lays out below in this edition of Global China.

Take it away, Tiff!

-Dave Shullman, Senior Director, Global China Hub

China Spotlight

Thank you, Dave! As the editor-in-chief of the Global China newsletter, I aim to provide my readers with some of the most important China news and analysis every month. My take is informed by my earlier experience as a journalist in China for almost a quarter century and the research and writing I do on China today. I hope you find our newsletter valuable.

Making nice with the US?

Has Beijing decided to make nice with the US? That’s a question I have been considering following a rash of recent positive news, including Xi Jinping’s decision to meet with a congressional delegation to China led by Chuck Schumer last week.

“China maintains that the common interests of the two countries far outweigh their differences,” Xi said to the bipartisan group of senators visiting Beijing.

And as Beijing has loosened up on issuing visas, friends in business have recently made their first post-pandemic trips back to China. Meanwhile, senior delegations from China and the Chinese Embassy in Washington, have been trekking to the place I work, the Mansfield Center at the University of Montana, despite its distance from the coasts.

How to understand all the amity?

China’s Sharp Power

A recent interview I conducted with the Hoover Institution’s Larry Diamond, a scholar of China’s Sharp Power—which he defines as “between soft power and hard power” and used to “penetrate open societies and compromise them, through corruption and coercion”—reminded me there is another lens to view this.

“Friendships are useful and important, but primarily they’re seeking strategic advantage. For a state like Montana, they would be trying to assess, get access to, become more aware of, the strategic assets,” said Diamond, who, with China expert Orville Schell, coedited the 2019 book, China’s Influence and American Interests: Promoting Constructive Vigilance. “They will say– okay what are the resources here? Do you mine anything that might be useful, for example, strategic minerals? Do you have ICBM silos?” (Montana has both.)

With companies? “They are trying to use American business to lobby the government of the United States, to adopt policies that will be favorable to China, and increasingly in recent years, to not adopt policies that will penalize China, such as export controls or outbound or inbound investment controls,” Diamond said.

‘Ideology over economic dynamism’

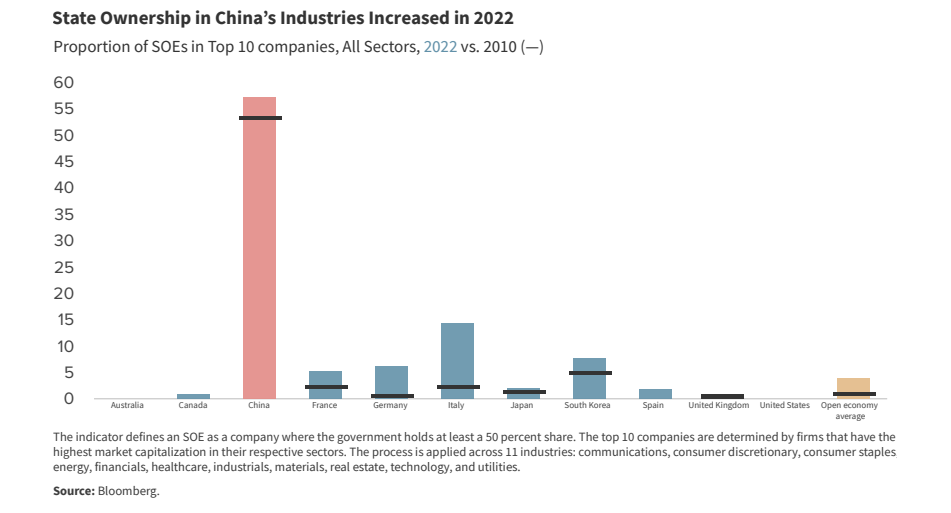

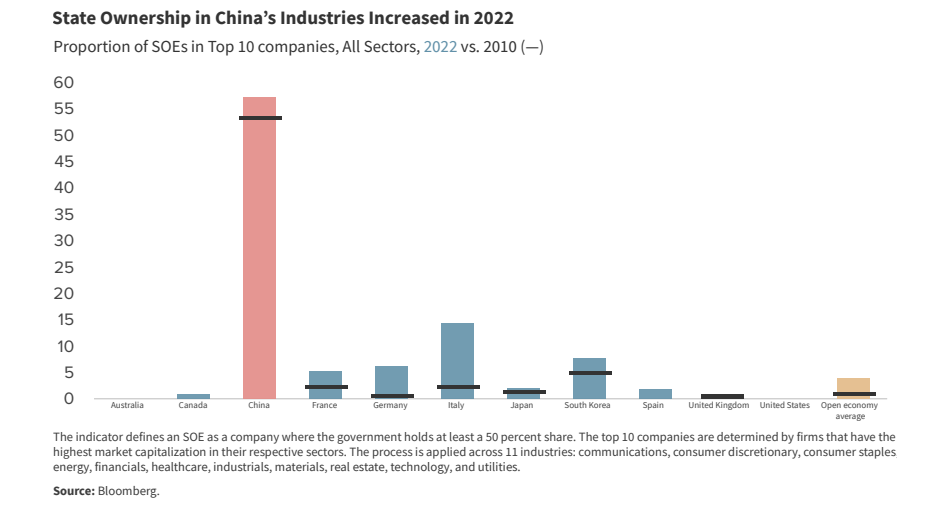

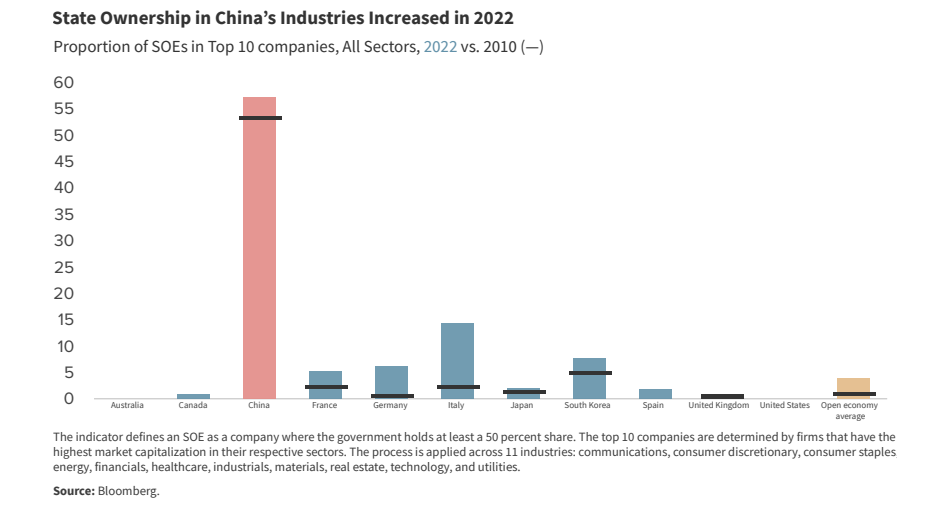

“Now, many around the world are finally coming to terms with reality—the Chinese economy is suffering in part because the Party continues to prioritize ideology over economic dynamism,” write the Atlantic Council Geoeconomics Center and the Rhodium Group in their recently released annual China Pathfinder. Their outlook for Chinese growth this year is the most pessimistic I’ve seen, predicting growth as low as 3%, well below Beijing’s official target of 5%.

You can see elements of sharp power in China’s Military-Civil Fusion policy, which “encourages Chinese civilian companies to acquire and pass along to defense firms dual-use technologies from foreign sources (read international companies and institutes) rather than developing them indigenously (through both legal and illegal means),” as described during a Global Tech Security Commission virtual event held in September.

‘Very different philosophical underpinnings’

China’s approach to business concerns American officials, including US Trade Representative Katherine Tai. “We’re two economies that are very structurally different, that are based on very different philosophical underpinnings. And so the issue of how we can achieve a coexistence that can be productive and constructive for the world is not an easy question,” Tai said at the Atlantic Council’s Transatlantic Forum on Geoeconomics, warning that global trade isn’t happening “on a level playing field.”

My take, as a former Beijing-based business correspondent: the new niceness has to do with the increasingly dire state of the Chinese economy. This simply is not a good time to alienate one of your biggest trading partners and it might even be a good time to back off on the politicization of business, a hallmark of Xi today. (The corollary is things can change fast-only some six months ago, Xi complained that the US “contained and suppressed” China.)

Transnational repression and the Uyghurs

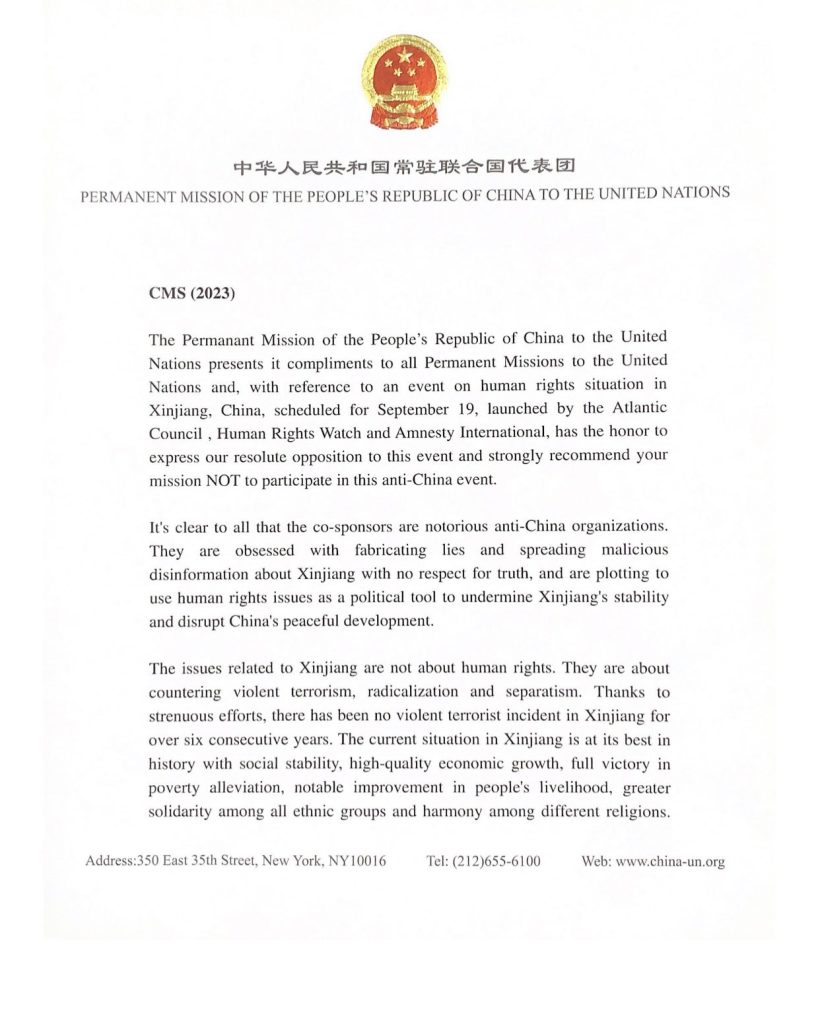

China’s transnational repression, seen most blatantly in its treatment of Uyghur people who live in and often are citizens of countries other than the PRC, was raised by the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project, together with Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International, in an event titled, “ From holding the line to a robust international response to the atrocities against the Uyghurs” held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly on September 19, 2023. The Chinese mission to the UN, trying to wield sharp power, issued a letter to other UN missions telling them not to attend.

Finally, nonresident fellow Niva Yau wrote about how new regulations protecting Chinese nationals overseas could instead be used to carry out repression.

So accept the niceness but don’t be naïve about what may lie behind it.

ICYMI

- Global China Hub deputy director Colleen Cottle appeared on The Chicago Council on Global Affairs’ podcast, “Deep Dish on Global Affairs” where she explored the expansion of BRICS, what it means for the grouping’s future, and how the US and its partners and allies should respond.

- Nonresident senior fellow Michael Schuman authored an article in The Atlantic titled, “China Is All About Sovereignty. So Why Not Ukraine’s?” where he argues that Russia’s war has confronted Xi Jinping with a stark choice between standing for principle or defending his strategic partner in Moscow.

- Nonresident senior fellow Jonathan Fulton hosted Mohammed Baharoon, director general of the Dubai Public Policy Research Center, for a new China-MENA podcast episode that explores a growing trend of de-escalation in the Arabian Gulf and how China is playing a central role in these shifting regional policies.

- Landon Derentz, senior director of the Global Energy Center, authored a blogpost arguing how the US can gain an edge on China in leading the clean energy economy by outpacing it in the development of hydrogen technologies.

Global China Hub

The Global China Hub researches and devises allied solutions to the global challenges posed by China’s rise, leveraging and amplifying the Atlantic Council’s work on China across its 15 other programs and centers.

Follow us on Twitter @ACGlobalChina