Hezbollah’s assertive posture in south Lebanon places UNIFIL in a difficult position

The recent revelation that Iran-backed militant group Hezbollah in Lebanon has constructed a 3,937-feet (1,200-meter) asphalted runway at one of its military bases is the latest example of the party’s increasingly brazen pattern of behavior, especially in the southern border district where a United Nations (UN) peacekeeping force has been deployed for the past forty-five years.

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) had its mandate extended for another twelve months by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on August 31. This has come at a time when tensions between Israel and Hezbollah are at their highest in seventeen years. Since UNIFIL has been deployed in south Lebanon since 1978, the “Interim” in its name became redundant long ago. However, the ability of the peacekeeping force to maintain stability in south Lebanon is coming under question given Hezbollah’s unprecedented level of assertiveness lately in the UNIFIL Area of Operations (AO).

Not only has there been an uptick in activity in recent months along the Blue Line—the UN-delineated boundary that conforms to Lebanon’s southern border—but, since late 2020, Hezbollah has also been establishing a new and visible military footprint in the heart of the UNIFIL AO. Hezbollah has expanded its positions along the Blue Line, which is manned by Green Without Borders, an officially registered environmental non-governmental organization linked to the party, which the United States sanctioned on August 16. Hezbollah has also established up to seven firing ranges in the UNIFIL AO, where militants practice their skills with various weapons.

This year, international and regional attention has focused on the heightened operational tempo along the Lebanon-Israel border amid fears of another war looming between the old enemies. In March, a powerful roadside bomb was detonated at the Megiddo junction in northern Israel, seriously wounding an Israeli Arab. The perpetrator, the Israelis concluded, was a Hezbollah militant who had infiltrated Israel from Lebanon and made his way on a scooter to Megiddo. He was intercepted by security forces on the return journey and shot dead.

In April, northern Israel was struck by the largest barrage of rockets since the month-long Israel-Hezbollah war in 2006. In May, Hezbollah erected a tent ninety-nine feet (thirty meters), sources tell me, inside the Israeli side of the Blue Line. In July, an anti-tank missile was launched across the Blue Line—an apparent reprisal for Israel’s physical annexation of part of Ghajar. This village straddles the Blue Line, leaving the northern half in Lebanese territory, although Israeli troops have been there since 2006. There also have been several attempts to damage the technical fence from the Lebanese side.

Israeli commentators have warned that Hezbollah’s actions erode Israel’s deterrence capabilities, given the lack of response. For example, Israel’s reaction to the rocket barrage in April was to blame Hamas and bomb targets in Gaza—115 miles (185 kilometers) south of where the rockets were launched.

Nevertheless, Hezbollah is careful to keep its provocations within a certain limit so as not to force Israel to react. Between 2000 and 2006, Hezbollah waged a sporadic but sometimes deadly campaign against Israeli troops occupying the Shebaa Farms, a mountainside running along Lebanon’s southeast border, using anti-tank missiles and roadside bombs. But Hezbollah’s overt actions over the past year have not drawn blood (Hezbollah did not claim nor deny the Megiddo roadside bomb attack).

Instead, Hezbollah’s operations are intended to confuse and vex the Israelis rather than spur them into violent action. The same could be said about the new airstrip Hezbollah has built in its sprawling Qalaat Jabbour training camp set in lofty mountains a couple of miles north of the UNIFIL AO. Speculation that Hezbollah was building a new runway emerged in November 2022. The rumors were confirmed in early September when Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Galant displayed satellite images of the new facility at a security conference.

Hezbollah had already constructed an airstrip in 2014 for its drones in the northern Bekaa Valley while fighting Syrian rebel groups across the nearby border. The 670-meter-long strip in the Bekaa was simple and functional. By contrast, the new airstrip is nearly double the length of the earlier version and includes formal runway markings and a helipad (Hezbollah does not possess helicopters, and runway markings are not required for drones to take off and land). The length of the strip is sufficient to accommodate small Short Take-Off Landing (STOL) cargo aircraft, raising the possibility that Hezbollah may seek to transfer weapons and equipment directly into its south Lebanon military base.

Such activity would not go unnoticed by the Israelis. However, it would pose the same dilemma as Hezbollah’s other bloodless but provocative actions along the Blue Line: Israel could easily destroy the airstrip. However, such a step would trigger a reaction from Hezbollah that could quickly spiral into a larger conflagration.

While the tensions between Hezbollah and Israel are playing out before the public through actions on the ground and an avalanche of threats and warnings from both parties and associated media coverage, the significance of Hezbollah’s emerging and increasingly visible military footprint in the UNIFIL AO has not been fully appreciated nor understood. Its new modus operandi in the UNIFIL AO contrasts starkly with its generally low-signature behavioral pattern in south Lebanon since 2006.

Although Hezbollah has had a military presence in the UNIFIL AO since 2006, it was invisible and generally confined to populated areas. In 2016, the first Green Without Borders position appeared on the Blue Line near UNIFIL headquarters in the coastal village of Naqoura. More positions soon followed, running eastward along the Blue Line. The Israelis claimed that the positions were military posts and insisted that they be shut down as breaches of UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which states that Hezbollah should disarm and no weapons outside those authorized by the Lebanese state should be present in south Lebanon. UNIFIL’s attempts to inspect the positions on the ground were often thwarted by Green Without Borders operatives, who blocked passage and said that the posts were on private property and, therefore, off limits to the peacekeepers.

However, around the end of 2020, Hezbollah escalated its visible footprint in the UNIFIL AO. The number of Green Without Borders positions increased significantly and began to take on a more prominent appearance. Near the border village of Aitta Shaab, Green Without Borders has erected a watchtower thirty-three to sixty-six feet (ten to twenty meters) high, dominating the surrounding landscape. The watchtower is one of six constructed in the past year. No attempt is being made to camouflage or disguise these positions. On the contrary, their clear visibility seems to be a deliberate attempt to flaunt Hezbollah’s presence along the Blue Line toward an Israeli military audience.

Perhaps the most manifest example of Hezbollah’s newfound assertiveness in the UNIFIL AO is the construction of firing ranges. Initially consisting of one-hundred-meter bulldozed strips in remote valleys, some are taking on a more entrenched appearance, according to sources I spoke to. One site near the village of Adchit al-Qusayr consists of a graded one-hundred-meter range with a covered shooting stand, several nearby sheds and checkpoints and swing gates to block unauthorized access. UNIFIL sources say the force has logged week-long training sessions at some of these ranges, where fighters employ a variety of weapons, from automatic rifles to rocket-propelled grenades. According to the sources, at least one of the ranges includes some form of underground facility for training purposes. The latest firing range emerged in March and lies a mere 2.5 miles (four kilometers) from UNIFIL’s headquarters.

Additionally, Hezbollah personnel are increasingly seen openly wearing uniforms and carrying weapons along the Blue Line. The Israeli military routinely photographs the fighters and displays the pictures at the regular meetings of the UNIFIL-hosted tripartite group, which brings together Israeli and Lebanese army officers. In July, Israeli soldiers filmed several uniformed and masked—but apparently unarmed—Hezbollah men patrolling the Lebanese side of the border.

Less visible, but equally telling, is Hezbollah’s quiet return to some of the locations where it ran military facilities before the 2006 war. The facilities were abandoned after the end of the conflict when a greatly expanded UNIFIL and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) deployed across south Lebanon. In one lengthy valley system in the UNIFIL AO, Hezbollah has established several positions tucked into narrow wooded valleys, leaving only the swing gate-protected entrances visible from the main road. At other pre-2006 military sites, small sheds fitted with satellite television dishes and solar panels have materialized, partially hidden beneath trees and accessed by newly excavated tracks. One small valley containing a handful of sheds has been sealed off with swing gates, denying access to local residents and UNIFIL peacekeepers alike.

It is unclear what spurred Hezbollah to adopt a more visible and provocative presence in the UNIFIL AO in late 2020 and early 2021. After all, Hezbollah has no shortage of training camps north of the UNIFIL AO that possess firing ranges 199 to 2,625 feet (sixty to eight hundred meters) in length, and there is no apparent need for additional ranges in the southern border district. The primary target of its assertive posture may well be UNIFIL itself, with the idea being to undermine, discredit, and weaken the force until it becomes irrelevant or spurs an exasperated UN Security Council to begin winding down the mission.

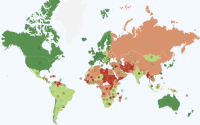

Thirty years ago, when Israeli troops occupied a strip of territory in south Lebanon, the then ten-nation 4,500-strong UNIFIL was part of the local community. Peacekeepers routinely bought goods in local stores, ate in restaurants, offered shelter to civilians during times of heightened violence, and dropped by the homes of village mayors and local officials to sit and chat over cups of coffee. But, today, the climate is far more hostile, which is mainly due to Hezbollah’s suspicion of the enlarged peacekeeping force and the sizeable presence of European troop-contributing countries. UNIFIL currently has some 10,500 peacekeepers from forty-eight countries, and they are dominated by NATO members such as France, Italy, and Spain.

Hezbollah is the dominant political actor in south Lebanon and has the necessary influence to easily turn up the heat on UNIFIL. Signs of local displeasure can vary from youths tossing stones at passing UNIFIL vehicles to more violent outbursts. Last December, an Irish peacekeeper was shot dead in his car during an altercation with a group of Lebanese men in a village north of the UNIFIL AO. The shooting was not a pre-meditated attack but the result of a situation that ran out of control after the UNIFIL peacekeepers lost their way late at night while heading to Beirut. However, the fact that a local Lebanese saw fit to open fire at a UNIFIL vehicle was emblematic of the hostility against UNIFIL that Hezbollah has helped stoke.

In conversations with UNIFIL peacekeepers, there is a rueful acknowledgment that force protection has come to trump mandate implementation. If Hezbollah members block a patrol from accessing a certain area, the peacekeepers will log the event and return to base rather than force the issue and risk a confrontation and possible subsequent backlash. There is a growing sense of disillusionment among some peacekeepers. They privately question the point of continuing the mission when it is unable to challenge Hezbollah’s presence and actions on the ground.

For example, UNIFIL has the right to freedom of movement in its AO as enshrined in UN Security Council Resolution 2695, which renewed the force’s mandate on August 31. But UNIFIL has not visited the firing ranges on the ground and has only observed them from helicopters because the peacekeepers do not want to risk a clash with potentially armed Hezbollah men. Instead, UNIFIL asks the LAF to organize a joint patrol to visit the firing ranges and other sensitive locations, shifting the onus of responsibility to the Lebanese state.

However, the LAF faces myriad problems of its own due to the economic crisis that has ravaged Lebanon since 2019, which has seen the salaries of officers and soldiers dwindle to almost nothing because of rampant inflation and the collapse of the Lebanese lira. The LAF leadership is struggling to maintain the daily functioning of the institution. Facilitating access for UNIFIL to visit Hezbollah-linked locations against the will of the party risks raising tensions unnecessarily, particularly as the LAF has received no guidance nor instruction from the Lebanese government on the issue.

Nevertheless, UNIFIL still serves an important role. The presence of some ten thousand foreign peacekeepers in south Lebanon helps ensure that international attention continues to be paid to this small, potentially volatile pocket of the Middle East. To an extent, the size of the force also serves as a form of deterrence. If UNIFIL was not present, Israel, for example, might have felt that it had more freedom to respond to Hezbollah’s moves along the Blue Line. If an all-out war were to erupt between Hezbollah and Israel, there would be ten thousand foreigners trapped in the middle, which should further encourage the international community to bring an end to hostilities as quickly as possible. Critically, UNIFIL’s role as interlocutor between the Lebanese and Israelis in the tripartite meetings is an essential—and probably the most important—component of the force’s mission.

After forty-five years in south Lebanon, UNIFIL is stuck between a rock and a hard place. Despite the usual diplomatic wrangling in New York over the resolution wording that saw UNIFIL’s mandate renewed, it will make little difference on the ground. UNIFIL has said that nothing will change operationally and that the force will continue coordinating with the LAF. Therefore, the status quo remains in place in south Lebanon. Hezbollah will likely continue its needling actions along the Blue Line to irritate the Israelis and possibly expand its visible footprint in the UNIFIL AO, safe in the knowledge that its audacity probably will go unchallenged.

Nicholas Blanford is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

Further reading

Thu, Apr 13, 2023

Hezbollah and its allies are more emboldened than they’ve been in nearly two decades

MENASource By Nicholas Blanford

The bottom line of this latest flare-up of violence along the Lebanon-Israel border is that Hezbollah, in coordination with Hamas, launched the largest barrage of rockets into Israel in nearly seventeen years without facing any repercussions.

Wed, Aug 11, 2021

Rockets were fired from Lebanon into Israel again. Another game of brinkmanship?

MENASource By Nicholas Blanford

While Lebanon descends into ever greater political, economic, and social turmoil, a new dynamic appears to be emerging along Lebanon’s simmering southern border with Israel. It potentially threatens the balance of deterrence that has helped prevent a major escalation of hostilities for fifteen years.

Thu, Apr 16, 2020

Lebanon and Israel: Blue line tensions

MENASource By Frederic C. Hof

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL)—now beginning its forty-third year of “interim” service in southern Lebanon—recently intervened to defuse an armed standoff between Israeli and Lebanese soldiers along the “Blue Line:” The line of Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon demarcated by the United Nations in 2000. These confrontations occur periodically. Why?

Image: United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) vehicles drive in Naqoura, near the Lebanese-Israeli border, southern Lebanon, August 16, 2023. REUTERS/Aziz Taher